A galactic imprint on exoplanet systems

A recent study shows that several properties of stars, including exactly how they orbit around the centre of our galaxy, can affect how likely it is that they host different types of exoplanets

Exoplanets have been found orbiting a wide variety of stars, with different masses, radii, and compositions. Since the emergence of such a diverse population, astronomers have been exploring how the properties of the star at the centre of a planetary system can affect the demographics and architecture of the planetary system which forms around it. Based on observations of such systems, and our current understanding of planetary formation, we know that the mass and metal-content of stars can affect what type of planets they host. A new study has shown that in addition to these stellar characteristics, the orbit of a star around the centre of the galaxy can affect planet properties too.

To understand how planets form, astronomers simulate the formation of planetary systems using computer models. The outcome of these simulations can then be compared to planetary systems observed by telescopes and satellites. Different simulations may contain different input physics and parameters, and simulations that better match the observations are considered to be a better representation of how planets actually form.

Some simulations predict planets are common, whereas simulations that model the physics of planet formation differently may suggest they are more rare. Similarly, planet formation simulations may predict that certain types of planets are more common than others, or that certain stars are less likely to have planets than others.

To compare these models to data, astronomers quantify how common different types of planets are according to observations. To do so, it is not enough to find exoplanets: it’s also necessary to estimate how many planets may have been missed — perhaps due to imperfect data — to determine the true number of planets in the universe. This parameter is known as the exoplanet occurrence rate, and is usually expressed as a percentage of a certain type of planet, at a certain orbit, around a certain type of star.

A recent study led by Jon Zink used data from the Kepler and K2 missions to investigate which stars have the most planets, and how different types of planets compare. For example, they found that stars that are smaller and cooler than the Sun have more Earth, Neptune, and Saturn-type planets than solar-like stars, whereas Jupiter-type planets appear to be broadly equally common around different types of star. They also confirmed the well-established link between the metal-content of a star and the occurrence of giant planets, and found that close-in planets of all types are more common around stars with a higher metal content.

While trends linking the occurrence of various types of planets to their host star mass and metal-content aren’t new, the study takes this a step further by investigating the galactic context of these planets.

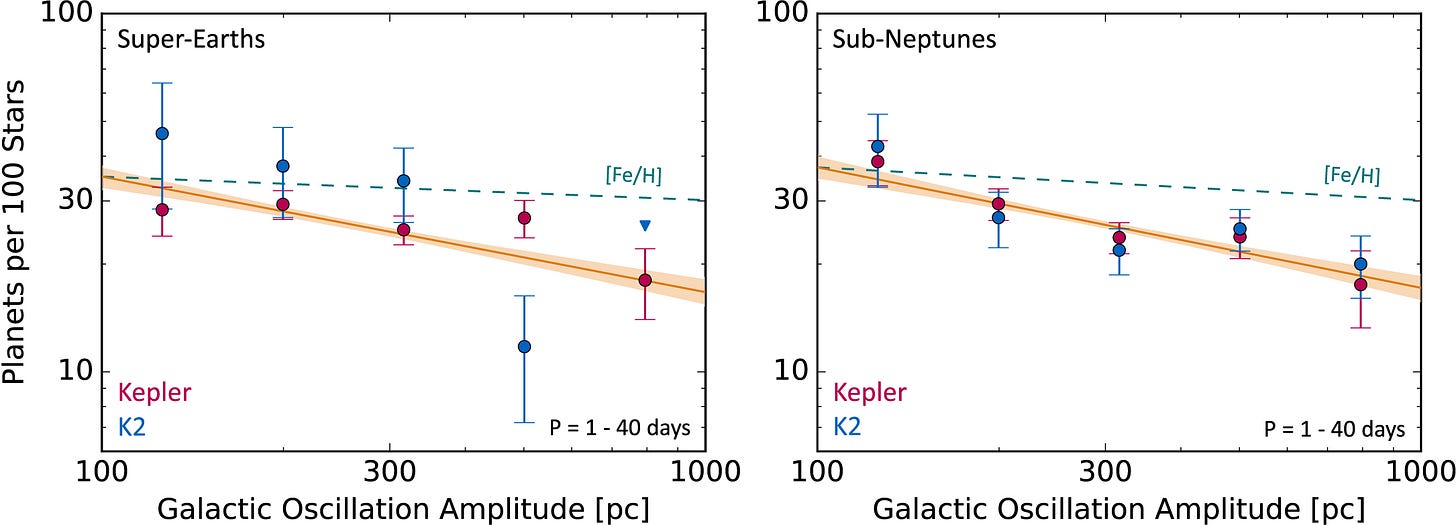

The most intriguing result from the study comes from comparing the exoplanet occurrence rate to their properties in the galaxy. In particular, Zink and his colleagues discovered a correlation between the galactic oscillation amplitude and the planet occurrence rate. Stars in our galaxy orbit the galactic centre, on orbits with periods of billions of years. As stars age, the dynamical properties of these orbits change, gradually deviating from a perfectly circular orbit. One of the ways in which this happens is that the stars begin to undergo vertical oscillations about a constant, ‘flat’, orbit relative to the plane of the galaxy — stars with a higher galactic oscillation amplitude undergo stronger such oscillations. The team led by Zink discovered that stars with a higher galactic oscillation amplitude appear to host fewer Earth and Neptune-type planets.

Dr. Gijs Mulders, Assistant Professor at the Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez in Santiago de Chile, an expert on the study of planet populations and not involved in the study, said to the Extrasolar Times:

“This work suggests that stars that have a higher galactic oscillation amplitude have fewer planets than those with a lower amplitude. This result is interesting because it shows the galactic context is important for whether planets form or not.

One big open question is why some stars have planets while other stars don’t. This work provides one new piece of that puzzle.”

Stars with higher galactic oscillation amplitudes are typically expected to have a lower metal-content — usually described by astronomers as the Iron to Hydrogen ratio or Fe/H — and it is therefore natural to ask whether the observed effect could be attributed to the previously mentioned well-known correlation between planet occurrence rate and stellar metal-content. However, the authors argue that the decrease in planet occurrence with galactic oscillation amplitude is significantly stronger than if it was caused exclusively by the varying metal content. It therefore appears that Zink and his colleagues have found some of the first evidence of a galactic imprint on the exoplanet population — even if the exact mechanism remains poorly understood. According to Dr. Mulders:

“What may come next is understanding the mechanism. Do stars lose their planets when they obtain their high oscillation velocity? Are fewer planets able to form around stars that have a high oscillation velocity?”

This new discovery is therefore likely to trigger new planet formation simulations that will attempt to explain the origin of this feature.

The study by Zink et al. has been published in the Astrophysical Journal in June 2023.